Not many books were read, but two of them were epic novels. One of them required 9 days! I usually have about 2 to 2 1/2 hours per day to read, with sometimes an extra hour on Sundays, when I often don't practice piano. I will begin with my regular five remaining Avon/Equinox authors, though this month I read Silverberg's last big novel. I have one large volume of his short stories remaining, and then I'm in to a few of his reissued pulp trash novels from early days. So Silverberg will likely be wrapped up by summer. Tubb and Bulmer will go on for years yet, as will Moorcock. And I still have at least ten more Malzberg pulp crime novels remaining.

First published as a whole in 2003, the 449 page Roma Eterna

is historical fantasy fiction, though it can't really be called a

novel. At least not in the traditional sense of that term. Silverberg

postulates that the Roman Empire managed to survive, rather than fall

apart as it did. Each chapter carefully explains how it managed to

overcome some of its biggest obstacles, such as the rise of

Christianity, the northern barbarian invasions, and the rise of Islam. The chapters were mostly published separately, then combined to make this one long story. It's always interesting to think how certain trivial events might have altered history if they had not happened, and this book is full of such ideas. I must admit that more than a few places were pretty boring to read, unless readers are fans of Roman history. I'm sure I missed many small connections, though I easily got the big picture. Again there is a great shortage of female characters. the ones that do appear seem to be there mostly to satisfy males for companionship and pleasure. Though hardly my favourite book by the author, it is a solid piece of writing by a man who was quite obsessed with much of history during his creative lifetime.

It felt good to jump into an easily readable novel by Bulmer, the 15th Dray Prescott one called Secret Scorpio. Though it many ways it's just more of the same, he is a good enough author not to repeat himself too often, and each volume adds something new. In

fact, Bulmer is a terrific writer, with a great sense of pacing and an

ever lurking sense of humour. Many of these stories rise well above the

usual pulp level encountered in so many books from this time. The guy

was a veritable work horse, with a very demanding publishing schedule.

Secret Scorpio introduces a fake religion, one promising riches and rewards

in this life, as well as in the afterlife. Many people can not resist

such promises, it would seem. Even people who should know better. For

once, the Emperor, whom Dray has insulted and thus has banished him from the

main city, is ahead of Dray. He does have his finger on the pulse of

his people, it would seem. Dray will have to face him again in the next

book. They do not like one another very much, and Delia, the Emperor's daughter and Dray's wife, is caught

between the two men. A good addition to the series.

Tubb's 2nd Cap Kennedy book, by contrast, seems to rehash many of the tales already told by this prolific pulp

master. Cap ends up becoming a mining slave, and must orchestrate a

break out before he can set things to right. A brutal race of reptilian

people are being led by a particularly greedy member of their race,

though he in turn is being tricked out of his mining fortune by two

humanoids. In addition to becoming a slave, Cap also has to fight in

the arena. How many times has this already happened in a story by

Tubb? The title is there to attract boys to the genre, but there are no

female slaves. Sorry, boys. There is only one woman in the story, and

she is there very briefly. This is a man's world. Girls keep out.

Oh, there is also a giant worm burrowing deep in the planetoid being

mined. We have to have a giant underground worm. No

marks for originality here. We've read it before, both in single

novels by Tubb and in his Dumarest series. I hope the other books in

this series can raise themselves a bit higher.

On to Michael Moorcock and the 2nd of his Colonel Pyat novels, called The Laughter of Carthage. The first book dealt with Russia and Ukraine in the years of the Revolution, roughly 1917-20. At the conclusion, Pyat was on a boat heading for Constantinople. It is a roundabout journey, but he makes it. His adventures in and around the city eventually involve him in the Greek and Turkish war, revealing how the Greeks were betrayed by the Americans and British during their failed attempt at conquering the Islamic nation. After a lengthy stay, in which he more or less adopts a 13 year old girl as his lover, daughter, and bride to be, they both head to Rome, and then on to Paris. Like

its predecessor, it is a very long book and covers a lot of ground.

Including the introduction we are looking at around 534 pages. In some

ways this story is as engaging as the first one, but in other ways it

isn't. Pyat's madness becomes much more evident in this volume, and his

asides and comments that interrupt the narrative flow grow longer and more manic. The story itself, when

it is told, is as fascinating as the first book. Another thing that

makes this volume a bit less fun to read is the amount of untranslated

foreign language rants and sentences that occupy the paragraphs.

French, German, Russian, and possibly other languages are used, and most

readers will have no idea what they say.

While

Pyat may be a fictional character, he is situated in the true

happenings of the 1910s and the 1920s. He meets many real characters

from the time, and sometimes becomes involved in events that actually

occurred. This is not historical fiction at all, but a unique way of

telling the complicated story of just what was going on in Europe at

the time. While no one person could possibly understand all of it, Pyat

has opinions on just about everything. His anti-Semitism and general

racism become even more outlandish. He supports the cause of the white (male)

protestant, and is against the pope and all that Catholicism stands for. And don't get him started on Islam. So

we are not too surprised when this Pyat character, who loves D. W.

Griffith and all that his films stand for, supports the work of the Klan

once he arrives in the US. At first I wasn't thrilled with the

American portion of the book, but by waiting patiently for several pages

the story became completely fascinating again. Despite its great

length, this is a series worth reading. at the conclusion of book 2

Pyat is about 22 or 23 years of age and about to be reunited with the

love of his life once again, after a lengthy interval. After a suitable break, I will look

forward to reading the 3rd book.

Burt Wulf lands in Vegas with a bang in Desert Stalker, a 1973 thriller that is the 4th in a series.

Malzberg hit his stride in this series at least one book back, and the roller

coaster life of this lone vigilante keeps the pace moving forward.

Though all the books are loosely connected, they are not tied down to the

same characters. In fact, most of the main characters are dead by the

end of each novel in which they appear. This time Wulf takes on the

Vegas racket, and takes a hotel and its crooked proprietor hostage.

Just when it seems like the story will focus around a kind of unusual

hostage situation, it explodes into a major pulp fiction action

adventure tale. Again the car chase is unique, and the way it is

resolved. Hollywood seems to know only one type of car chases; Malzberg

is way ahead of them. At one point we see a bit of life come back into

Wulf, who has been essentially a killing machine since the overdose death of

his new York girlfriend. He has another female friend from two books

ago, whom he met in San Francisco and managed to pull away from drugs.

He calls her in a moment of desperation, badly needing to talk to

someone. And so we are confronted with at least a trace of humanity reawakening in the man. There are 14 books in the series.

Moving on to my free reading for the month, I managed to get through [ ] books. The first one is called Seven Brief Lessons In Physics, by Carlo Rovelli, a book suitable for non-science majors to help them understand the modern world. Beginning with simple but very effective explanations of Relativity and Quantum Mechanics, the book (really it's barely a novella) moves outward to cosmology and inward to atoms and electrons. It succinctly summarizes our knowledge to date in the most simple terms I have ever come across. The book would be suitable for Gr. 11 Physics students, or anyone who has even a passing interest in what has been going on for the past hundred years or so regarding our material world.

A simple and easy to understand primer on the state of modern physics.

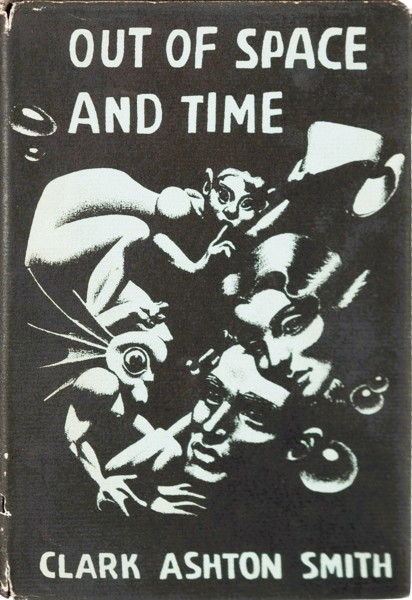

Next came Clark Ashton Smith's 2nd collection of shorter tales, called Out of Space and Time. It was published in 1942, though Smith had pretty much done with writing by 1936. Heavily influenced by Poe, he wrote in the tradition of Lovecraft, Dunsany, and Robert E. Howard. But he definitely outclassed those latter writers, except for Dunsany. Smith's horror fantasy stories are unique in the literature, and well worth seeking out. This collection has 20 tales. One of them, "The City of the Singing Flame," is given in its early shorter version and in its revised novella version. I read the novella version. A man steps through a kind of dimensional warp in time and space and emerges in a fantastic landscape, with a city in the distance that sings like a siren to any who hear. Filled with good descriptions of strange people, places, music, and architecture, it ends with the complete destruction of what should have been the gate to Utopia. I can see the early stories of Jack Williamson being heavily influenced be Smith's writing to mention A. Merritt. "The Second Internment" is straight out of Poe's stories, as a man who fears premature burial has it happen to him not once, but twice. The description of him suffering inside the coffin is true horror writing at its finest. "The Chain of Aforgorman" is an Orientalist horror/fantasy tale about a man who uses a rare drug to achieve his goal of reading from a forbidden text. Guess where it gets him? Not to heaven, at any rate. "The Unchartered Isle" is a shipwreck fantasy, about a man who encounters some very strange humans where he ends up landing. Though he leaves with proof of his strange adventure, still no one believes him.

Once we get to the Zothique stories, we have come upon some of the finest fantasy horror fiction to have ever been penned. "The Dark Eidolon" is a prime example of Smith's ability to create a kind of fiction that has never been surpassed, even by Fritz Leiber. A vengeful and powerful wizard takes revenge of the cruel and selfish king that once wronged him. Though the wizard does take his revenge, despite dire warnings from his patron evil god, a few unexpected turns make his revenge far from satisfying. Great stuff!

Another tale from the continent of Zothique is "The Lost Hieroglyph," where a hapless 2nd rate astrologer takes his final long and rather complicated journey into the hereafter. One thing (of many) that I like about Smith's writing is that his endings are often unexpected and unusually harsh at times. Assuming a certain ending, the reader is likely to be surprised. "Sadastor" is very much in the tradition of Lord Dunsany, a short piece that is mostly descriptive. "Oh," says one creature to another, "so you think you are woeful. Well, wait till you hear my story...".

Smith is again at his very best in the relatively short "The Death of Ilalotha." A handmaiden to the Queen, both these women are in love with the same man. He flees for a week to recuperate. It is the hand maiden whom he loves, and is at a loss at what to do. When he returns he finds Ilalotha dead, as well as the King. A 3-day orgy and drunken feast is just ending, apparently the way funerals are run in this kingdom. Again there is a truly wonderful ending, as readers expect something quite different. A real treat to read! By comparison, "The Return of the Sorcerer" is pretty much pure Lovecraft, and nowhere near as good. Twin brother sorcerers fall out and one kills the other. The dead one comes back for some revenge. But he has been cut up into pieces, which have been buried separately. So it takes him some time to get his act together, so to speak.

"The Testament of Athammaus" shows a humourous side to Smith. A city's axeman tells the tale of a criminal whose head would not stay attached to his body. Each time the man reappears from his grave, the neck area becomes more deformed, until at last his head comes back attached at his chest. Needless to say, the citizens are quick to abandon the city after the third reincarnation. Athammaus is the last to leave. He now has the same job in a different city. Another somewhat light-hearted tale is "The Weird of Avoosl Wuthoqquan." Avoosl is a money lender, and somewhat on the greedy side. After refusing to give pitiful beggar a coin, something that always obdes ill in a Smith story, the beggar predicts an unholy death for the man. One day a thief comes to Avoosl, selling him two beautiful emeralds. But the emeralds are called back to their owner, and Avoosl follows them, not wanting to lose their investment. He discovers a veritable Aladdin's cave of jewels, and literally bathes in them. However, he soon meets the even greedier owner of the jewels. "Ubbo Sathla" concerns a jewel found by a man in a London antique shop. Could it possibly be the jewel that old texts say was once owned by a powerful wizard eons ago? Why of course it is! And by staring into it, the new owner of the jewel gets to meet his ancestors from way back.

The next story is a SF novelette called "The Monster of the Prophecy." A down on his luck London poet contemplates jumping into the Thames one night. He is interrupted by a man who tells him that he is an alien from the Antares system, and that he wants to bring back a human with him to help fulfill a prophecy. Off they go, and a large part of the story is a description of the city state where the alien, having timed his appearance with the strange man from Earth (the people from the Antares system have three legs and five arms and three eyes), is able to claim leadership over the people. But things don't go smoothly for either the new leader or the man from Earth. A decent enough story, but not the kind that Smith excels at. For that we turn to the final longer tale, "The Vaults of Yoh-Vombis." Forget "Alien." For a really good SF/horror story, look no further than this tale of a group of Martian archaeologists researching a 40,000 city on Mars. Like many Martian cities, this one has a vast underground component. What a great film this would make! Though the ancient city dwellers of Yoh-Vombis are long gone, there is still a very nasty lifeform dwelling down there beneath the old city. Classic Smith story telling!

Next up was Solaris, the 1961 novel by Stanislav Lem. Unlike the two movies I have seen loosely based on the book, the novel is about the planet Solaris. As Lem himself stated, "If I wanted to write a romance, I would have called it "Love In Outer Space." Two quotes by Dr. Snaut early on clarify things nicely. "We don't need other worlds--we need mirrors." In other words, humans are a long way from claiming to be ready to visit other planets and to understand them. And then, "We are unlikely to learn anything about it [the planet Solaris], but maybe about ourselves.

This is hardly the first great alien contact story I have read. There are excellent ones by many of the Avon/Equinox authors, such as The Man In the Maze by Robert Silverberg, and The Shores of Another Sea and Unearthly Neighbours by Chad Oliver, to name only three. But Solaris is different in many ways. For one thing, humans have already been studying the great ocean planet for decades before Dr. Kelvin comes aboard. His psychology degree is useless in his search for answers as to why people are appearing on the planet (he does seem to be a bit thick), since his entire outlook, and that of other humans trying to communicate with Solaris, is totally human centred. They have no reference point other than themselves in which to experiment. Thinking outside the box, in this case, leads quickly to so many quack theories that are untestable that the subject can not really proceed in any direction but the usual one. Lem is painstaking in describing the planet, and takes a full 38 page chapter to let us know what has already been learned. Besides this chapter, there is much more about Solaris, too. But none of it allows for any kind of communication. Oliver's Unearthly Neighbours comes closest to this conundrum,and would make a good companion read with Solaris. But Lem offers no plausible answers. His only solution is for Kelvin to stay on the station and keep trying. By now he has realized the futility of getting back his wife/girlfriend, but the great ocean (there is some land on Solaris, too, by the way) and the mystery of its existence will not let him return to Earth. And so he stays on at the end, and will continue to experiment. A true "science" fiction book, and one worth more than one reading. And forget about the Soderbergh film, which has absolutely nothing to do with what Lem is attempting to write about.

That's it for this month. I am coming towards the end of my Silverberg books, with only one more SF story collection remaining. When that author is finished, I will replace him with a reread of all the works by Fritz Leiber, still a great favourite. Besides the man who coined the term 'Sword and Sorcery', and who wrote many of the best stories in that genre, he is also a great SF author, as well as a horror writer. His stories are often filled with humour, too. So expect lots of Leiber in the months ahead.

Mapman Mike

No comments:

Post a Comment