Seg The Bowman is from 1984 and is 142 pages long, not including the final glossary. This completes the Pandahem Cycle Part 2 of the Dray Prescott series. In this story we get Seg's side of the story after he and Dray were separated at the end of Volume 29. 29, 30, and 32 detail Dray's adventures, while #32 tells Seg's story. Seg has rescued who he believes is the Queen's handmaiden, and pledges to deliver her safely back to her home. The King and Queen were killed in the cave adventure (#28). Seg's adventures pretty much mirror the kind of things that usually happen to Dray, and Seg is pretty much the same hero type as well. Other than his romantic interest in Tilsi, we could pretty much substitute Dray in this adventure. This is unfortunate. At least the volume about Deliah's adventures provided contrast to the adventure series. New characters are introduced, both good and bad. There are prisons, escapes, injustices, creatures and a battle. Two pygmy forest natives add some zest to the proceedings, as they wish to escape the jungle and assimilate into the outer world. A good entry in the series, but there is very little that is very new. Seg makes a landmark bow shot and marries Tilsi, who, it turns out, really was the Queen after all.

A personal blog that discusses music, art, craft beer, travel, literature, and astronomy.

Friday, 1 August 2025

July Reading Summary

Friday, 31 May 2024

May Books Read, and Annual Update

I commence my 9th year of reading works by Avon/Equinox SF Rediscovery Series writers. I still have 5 writers on the list, though Silverberg is nearly done. Malzberg and Moorcock have about a year to go, while E C Tubb and Kenneth Bulmer are still in for the long haul. This past year I managed to add 60 books by the Avon authors to my list, which is now at a total of 829. I doubt I'll make it to a thousand, but one never knows. Books unrelated to the SF series equaled the series books for the very first time this year, as I also got through 60 books of free reading, many of them from the Delphi Classics series. Added to the accumulative series total, I have now read 226 books unrelated to any particular project. And total books read from June 2023 to end of May 2024 is 120. That's a book every three days!

This month I finished the 'required' reading (5 books) and was on to freestyle by May 14th. Only 5 of the 24 Equinox/Avon authors remain for me to finish up within the stable of SF writers, as well as dozens from the Delphi Classics series.

Wednesday, 1 March 2023

February Books Read

Despite being a short month, and with three astronomy nights in there as well, I still managed to read 11 books; seven from my Avon/Equinox SF Rediscovery project, one off the shelf, and three from Kindle. Needless to say my actual miscellaneous shelf is now down to about five books, from about fifty not so long ago. Almost everything I buy now is on Kindle, at least 95 % of my book purchases.

The month always begins with Robert Silverberg, but this time he collaborated with Isaac Asimov. There are at least three such books I will be reading in the course of completing the project (someday). Nightfall is from 1990, and was the first collaboration. Very loosely based on a 1940s short story by Asimov, the novel is the story of a post-holocaust society, much like the ones written by nearly every other SF author, including Algis Budrys, John Christopher (his specialty), Edgar Pangborn, and so on. The differences here are worth noting, however. This is an alien society, much like humans on Earth, but they are not humans on Earth. They live on a planet with six suns, and dark skies are unknown here. Except once every 2049 years. Still, after the Mad Max movies, and so many previous tales of the mayhem that will ensue when society collapses, I am surprised that this book was written. Of course without those big names on the cover, it is doubtful if it ever would have been published.

Isle of Woman by Piers Anthony was next. From 1993 comes the first book in yet another epic series, this one under the title of Geodyssey. This first book is 470 pages long, including the author's afterword. In his own words, this is 'history light,' and the simple writing seems aimed at a high school audience. He said that he hated history in school, finding it dull. He wanted to make it more interesting with this series, which begins with a story from 3.7 million years ago, up to one from the near 'future' of 2021. Probably something I would have found interesting around Grade Ten or Eleven. I have one more Anthony book in my collection, the second book of this series. At that point, I will likely stop reading Anthony's series. I will carefully check out any remaining single novels before buying anything else by him. 59 books read so far, which is not even half of what he has written. This book wins cover of the month.

Cover of the Month for Feb. 2023 goes to artist Eric Peterson.

Monday, 28 February 2022

February Reading

It turned into an amazing month for reading, as I got through no less than 14 books. That's an average of two per day! Some excellent reading in there, too, including the first two Oz books, with original illustrations.

The new month always gets started with something by Silverberg. I have collected all 10 volumes of Silverberg's shorter fiction, and read Vol 4 last month (which is really Vol 5, as the first volume was not numbered). It contains 14 stories from 1972-73, lasting for 411 pages. I had read only one of them previously. The best them is listed here: The Dybbuk of Mazel Tov IV, where a Jewish colony on another planet has to deal with the reappearance of one of their recently dead in the body of an intelligent native. A wonderful story; Ship Sister-Star Sister is a very good story about the first starship to leave Earth for the great unknown. It carries a female telepath, while her twin sister, also a telepath, remains on Earth. This becomes the main way of communicating from space. Very well done; This Is The Road is the first of two novellas in this volume, and seems to be a perfect example of what a good novella should be. A group of four people are travelling west along a road to escape pillage and worse from invading barbarians (does this sound contemporary enough--Russia invade Ukraine as I write this). They come up against a wall built to block the road, and must decide what to do. An excellent story, well contained within itself; and In The House Of Double Minds, an intriguing right brain/left brain story. This book also wins best cover on the month.

Next up was a very well done stand alone novel by Piers Anthony, lasting over 520 pages. Called Tatham Mound, it is a story about a Florida Indian tribe in the mid 1550s. Well written and well researched, the fictional story is based upon people who were actually uncovered in the excavation of a rare burial mound find in northern Florida. This is like something Silverberg might write, or Harry Harrison. The 20-page concluding essay by the author is also well worth reading.

Stainless Steel Visions is a collection of 13 short stories by Harry Harrison, as well as a short essay by the author on what makes a short story good, and what doesn't. I had read many of the stories in other collections, but I will list three of the new ones that I really liked. Toy Shop is from 1962, and is 8 pages long. A fun tale about trying to get one's important invention noticed. Commando Raid is from 1970, and is 14 pages long. Were there lessons learned from the Vietnam War? Harry Harrison learned them, but apparently not everyone who should have did. The Golden Years of the Stainless Steel Rat is from 1993. It is 20 pages long. A prison break is nothing unusual for slippery Jim deGriz. But this time he springs the entire geriatric population. The Stainless Steel Rat (and Angelina) are still in top form, despite the aging years.

I began another new series by Kenneth Bulmer, writing under the name of Bruno Krauss. It's a series about German u boats in early WWII, before American got involved. Their mission is to sink British ships. It must have surprised a lot of people when they out that a British writer penned the series. The first book is called Steel Shark. The missions are harrowing, both for the crew of the submarine, and for the British sailors above, and we get good looks at both sides of the coin. I have always believed that submarines attempting to sink civilian ships is a very cowardly undertaking, and the book didn't change my mind about that. Is it a coincidence that Das Boot, the incredible movie about the same subject, came out in 1981, three years after Bulmer's series was underway? I think not. Though the movie is based on a 1973 novel, Bulmer's books were quite popular, especially in Germany. I will likely read one or two more eventually, but not the entire series (8 books).

Next was a pretty terrible SF pulp novel by Tubb, from 1953. This man could crank out incredible stories one after another, but not this time. Maybe he had the flu when he wrote it. The Wall is a mysterious barricade blocking access to the heart of the galaxy, where the answer to eternal youth lies. It's an interesting enough premise, but it handled very routinely, and the book never really gets things into gear. At least at 130 pages, it was short.

Even Jack Williamson turned out a clunker for me this month. Beachhead is from 1992, written when Jack was 82. It's about the first human trip to Mars. It is actually worse than the previous pulp novel by Tubb, which I awarded two stars. This one got one and a half. Avoid.

After a disappointing start last month to Michael Moorcock's Elric series, the next book I read was much improved. Written in 1989, many years after the first novel, Moorcock returned to the series to fill in some gaps of events during Elric's years of travel. Since I am trying to read them in chronological order (not the order in which they were written), the next book was The Fortress of the Pearl. It seems to be a compendium of styles, from Lovecraft, Dunsany, E R Eddison, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E Howard, Frank Baum, and Fritz Leiber, not to mention Homer, who started it all. They actually blend well! My oversize version is 164 pages, but the original paperback version is 248 pages. A really great read!

The last novel related to my Avon/Equinox authors was called Chorale, written by Barry Malzberg. It is a weirdly structured time travel novel, where the people of the near future have to keep going back in time to make certain that important events actually happen. While the book gets bogged down in its own philosophy (did the past really happen, or did we create it from the future), there are enough moments of brilliance to make this a compelling read. A man is chosen to go back in time and reenact key events in the life of Beethoven, the great composer. Quite a challenge, since the man neither speaks German, is a musician (in fact he doesn't care about music at all), and is more than slightly demented. There are several hilarious events and moments, all dark and conspiratorial, but we do end up learning a good deal of Beethoven, and the almost hideous times in which he lived (especially regarding public health and personal grooming habits). Definitely worth checking out, even for non musicians.

After reading my required 8 books in my ongoing project (see separate website for the Avon/Equinox series), I turned my attention to unrelated books from my "miscellaneous" shelf. I managed to read six, including two by female writers. First came Patricia Highsmith's The Price of Salt, an incredible and memorable tale of a young woman meeting an older woman and falling in love with her. They end up going on a road trip together across the US. Written in 1952, this is probably the best book I read all month (a tie with one other--see further down). Exceptionally well written, and we also got to watch the 2013 film, called Carol, based on the book.

The Dragon Scroll, by Irina K Parker is part of a very long series of murder/mystery books taking place in 11 C Japan. I read several many years ago. Though this one was written later, it is the first of the books chronologically, and I have had it on my shelf for many years. The parts about Japanese society, customs, and life styles are well researched and form the main interest for reading these books, much in the same way that Pat McIntosh writes her mysteries in medieval Glasgow. The book was okay, but as per most modern mystery stories, there are simply too many murders for one book. Find something else to keep a reader's interest, instead of continually murdering someone else.

I dipped into my vast library of Delphi Classics on Kindle for the next four books. First of these was called Toppleton's Client, by J K Bangs, his second novel. Written in 1893, it is a very funny tale about a one man trying to help a spirit regain his body, which was stolen by another spirit 30 years earlier. Extremely well written, and the premise is given sufficient time and breadth to develop before we really get into the nitty gritty of things. The ending was actually a surprise, but perfect for the story. Not only are Americans lampooned, but the British who receive them are raked over the coals as well. Courts and lawyers are not spared either, but it's never nasty, only fun.

Next came a serious work, A Man From The North, by Arnold Bennett. Partly autobiographical, it's about a man coming to London from a smaller city, and hoping to become a writer. He takes a room, gets a clerk's job, and occasionally sends in an article or short story to a publisher. They are always rejected. The story follows him for years, and was a surprisingly good read. The author allows us good access to the man's inner thoughts, and his constricted lifestyle, with occasional episodes of hope, keep us reading on page after page. He has no real friends, seems unable to meet women, and has no sense of true ambition to work at being a writer. However, he has a strong sense that he is far above his fellow men, despite his lack of success with women and with writing books. If he didn't have his strong ego he would undoubtedly fall apart quickly. The book could also be called Ambitious Hopes Meet Reality. Highly recommended.

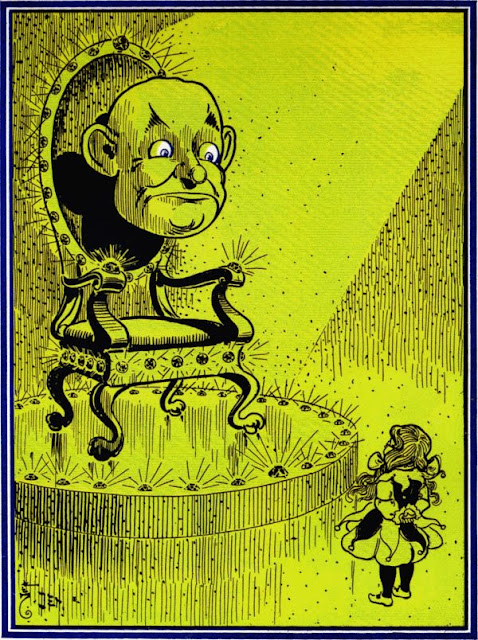

I finished off the short month by reading the first two Oz books. I have read The Wonderful Wizard of Oz before, but only in a text version. This time I had access to all of the original art that accompanied the story. There is so much to love about this book, and it certainly remains as relevant today--to kids and adults--as when it was first written in 1900. There is wonderful satire, brilliantly imaginative locations, characters, and adventures, and a total sense that somehow this is all real, somewhere. A must read, for everyone.

Dorothy, with her green spectacles, meets the Wizard of Oz.

Echoing the adventures of Homer's Ulysses, our four heroes become bogged down in a field of poppies that make two of them very sleepy.

Never having read The Marvelous Land of Oz, the 2nd book in the series, I pressed on. Though not as good in many ways as the first book, the 1904 sequel has its own rough charm. The humour is back, and a different artist takes over. The Scarecrow is chased off his Emerald City Throne by a band of girls with knitting needles, and sets off westward to find the Tin Man and get his help. The girls chip off all the precious stones from the walls of the Emerald City, force the men to do all the home labour, and the women relax and make fudge. After an unsuccessful attempt to get his throne back, the Scarecrow and friends set out to get Glinda's help. New characters in book two are Jack Pumpkinhead, H M Wogglebug, T. E., a bad witch, a sawhorse, and a flying thing made from palm leaves and two sofas, and a boy who turns out to be a girl. All the greatest fun one could ever have, so read it soon.

Two illustrations from The Marvelous Land of Oz, Book 2 in the series.

Mapman Mike